Muhammad Elsadany stood silently, observing his high school classmates frantically tie their peer to a palm tree. Happy birthday, they jeered, as water sprayed over the boy’s tightened face. Elsadany found himself fascinated by this strange psychological interaction (why was that act a mark of celebration?) – and many others, which were rife in his all-boys boarding school in northern Egypt.

Away from his family and familiarity for the first time, Elsadany was curious about the strangers that were his peers, and why they thought and acted in a certain way. Soon the barrier of unknownness was broken, as some of his classmates approached him to be friends – solely due to the color of Elsadany’s skin, which was whiter than their own. “I became interested in how we perceive other people and how people behave. Why would someone like another person just based on their outer appearance without even talking to them?” Elsadany remarks.

Elsadany soon became deeply interested in psychiatry, and although now a fourth-year PhD candidate in Jake Michaelson’s genomics and computational psychiatry lab in the Department of Psychiatry, he never wagered he would end up on the research side of the field. He originally dreamed of becoming a psychiatrist, but had his mind quickly changed after attending one day of medical school, which is slated right after high school in Egypt. Upon witnessing the people-packed lectures, Elsadany realized he wanted a smaller learning experience, mirroring that of his high school.

Pulling himself from medical school, he would find that experience as an undergraduate studying computational biology and genomics at the University of Science and Technology, Zewail City, Egypt. While there, Elsadany still had an itch for medicine, thinking he would use the degree to design and develop drugs one day. Research and becoming a researcher had yet to crystallize in his mind as the path for him.

In contrast, his friends’ paths had crystallized, and Elsadany watched as they applied to PhD programs during their senior year of college. Suddenly feeling the weight of peer pressure, Elsadany decided to do the same. Two days before the application deadline, one of his friends casually mentioned Iowa State University as a potential contender. Back home later that evening, all Elsadany could remember from the conversation was the word “Iowa” – and after a quick Google search, he unintentionally applied to the University of Iowa. Fate or possibly dumb luck must have been behind that memory lapse because Iowa was his first interview and acceptance.

In August 2021, Elsadany traded the deserts of Egypt for the farmlands of Iowa, arriving as a first-year PhD student in the Interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Genetics. During their first year, all students are required to rotate through – or, try out – various labs to find the best fit. Elsadany immediately wrote off his first rotation, which was randomly slotted for the Michaelson Lab, thinking he was going to be overwhelmed by the transition. To his surprise, the lab was a perfect fit. “I ended up liking the lab because of the environment. It was a small lab and everyone was very introverted and truly nice. And they were not just pretending, they were genuinely nice,” Elsadany explains.

Elsadany’s first project in the lab aimed to abrade the trial-and-error process that is drug prescription and reaction, utilizing genetic information to predict what medications a patient would best respond to. “I was interested in this project because I tried a lot of different medications and I know how long it takes to change a medication and deal with the side effects and all that,” Elsadany recounts. The project was based on the principle that medications cause a change in gene expression – that is, they cause different genes to turn either on or off. Ideally, patients’ gene expression should be different from what the drug is known to alter gene expression levels to. That way, the drug can change their gene expression, and lead to optimal biological responses and effects.

While personally meaningful to Elsadany, after two years, the project began to stall. The medical history files from the patients were convoluted and unstandardized, the variance in the common and trade names and doses of the medications proved difficult to wrangle, and the results couldn’t be replicated in different datasets. The problems continued to compound and Elsadany, who never wanted to do research on his own volition, decided to explore other options. He applied to several jobs outside of academia and even landed a few positions. However, something held him back from clearing his belongings from the Michaelson Lab. “I realized I did like research and I did like the questions the lab was asking. Maybe it was just the project I was working on, which I felt I had done all I could.” Elsadany recalls. “Maybe there was more to be done here.”

So, Elsadany turned down the offers, shifted projects, and began investigating individuals who are twice-exceptional – that is, they have a neurodevelopmental condition like autism or ADHD and simultaneously have high cognitive abilities. The lab deeply phenotyped these individuals, collecting information on their genetics, brain structure, IQ, language abilities, and interpersonal skills. Combing through all the data, they discovered individuals who are twice-exceptional have a higher suicidal ideation rate. Elsadany dug further himself, finding that suicidal ideation is linked to processing speed, which is a cognitive measurement of how people receive and understand information.

“My idea was that the higher suicidal ideation of those individuals was not because they were twice-exceptional, but because they have a lower processing speed. If we can understand what’s happening in the brain because of processing speed, we could potentially learn something about suicide that we don’t already know. Then, we could begin to ask if we can enhance processing speed and therefore decrease suicide ideation,” Elsadany says.

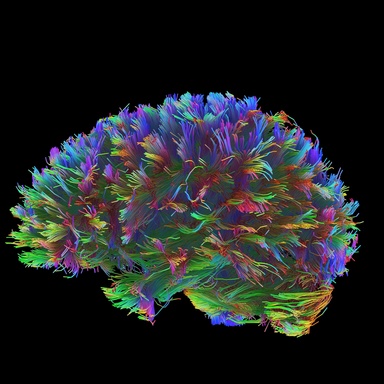

To capture processing speed on a molecular level, Elsadany has used advanced neuroimaging sensors to visualize neuronal tracts in the brain. These tracts bridge different areas of the brain, and relay information, directly impacting processing speed. Elsadany and the lab have already begun to hypothesize what is the biological culprit behind the relationship between lower processing speed and high suicidal ideation in twice-exceptional individuals.

At the same time, Elsadany notes that IQ tests can also tell a story about processing speed. Given that IQ tests can be costly and timely to administer, the lab has discovered language performance tests are a solid proxy for measuring cognitive abilities like processing speed. Altogether, Elsadany is focused on further fleshing out the genetic and molecular role of processing speed, and how a greater grasp on the mechanisms can lead to practical interventions and improvements in the quality of neurodiverse lives.

Like a switch, his passion for psychiatry was reignited. “The project exposed me to different data types and it helped me learn a lot of different stuff,” Elsadany voices. “I gained a broader understanding of psychiatry and it helped me navigate things and find passion and motivation." Spoken like a true psychiatry student, he also credits a successful medication trial, “I’m not going to lie, it’s also 50 mg of Sertraline [an anti-depressant].”

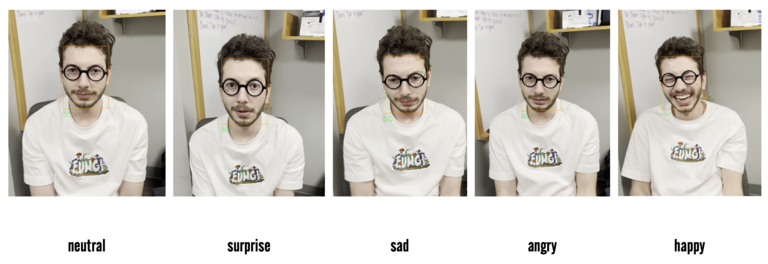

Beyond finding passion and finally feeling like he wanted to be a researcher, Elsadany started to see his own reflection in the data. “After spending time with the data, I began to wonder, do I really fit in with this population or not?” he says. He decided to find out and, at the age of 25, he was diagnosed with autism. Finally, everything made sense – including the fascination he had with classmates’ strange interactions, which he would jot down in a notebook. “Throughout all of high school, I was just taking notes and trying to understand people. I had a notebook and I used to write about what people did in different situations. Later in life, I realized it wasn’t me trying to understand people, but trying to learn how to behave in a way that doesn’t look odd.”

Now equipped with personal and academic satisfaction in his research, Elsadany looks towards the future with an open mind, while reflecting on his past – and the series of chance encounters that led him to the point of peaceful contentment.

“I never planned to be anywhere. I am embracing all those challenges that told me this is not what it should be or where I wanted to be,” Elsadany reflects. A few days ago, Elsadany read a line in a poem that resonated with him: I learn by going where I have to go.

[The line is from the poem “The Waking,” Theodore Roethke].