Our goal is to better understand the molecular and genetic interplay between sex, gender, and neurodevelopment. Biological sex is a well-established factor that has a profound effect on how developmental and psychiatric conditions present. For instance, autism is highly male-biased (4:1) and anorexia nervosa is highly female-biased (8:1). What is less understood is whether a continuous (rather than binary) view of sex and gender can yield additional biological insights into these and related conditions, and more generally into how the brain develops.

To make progress in this research, we are partnering with members of the LGBTQ community because of their rich diversity along the axes of sex and gender. It is important to emphasize that just as the examples of sex bias in autism and anorexia do not "pathologize" being a male or a female, respectively, our research does not pathologize sex and gender minorities (SGMs). This diversity simply provides a new window through which we can learn more about the role of sex and gender in neurodevelopment.

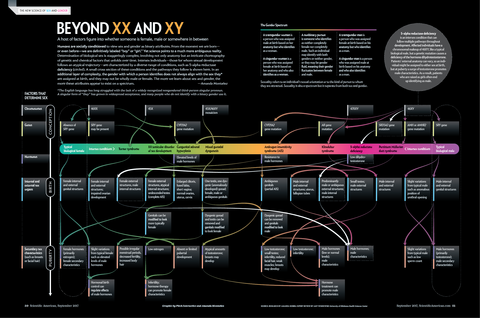

"Visualizing Sex as a Spectrum"

Scientific American has put together an incredibly thorough diagram of how sex determination can be visualized as a continuous spectrum, rather than the binary view of XX female and XY male.

Read More about the complexity involved in this topic.

Why are we interested in this research?

Sex and gender have a long history of being important to the understanding of development3. Societal changes over the past several decades (and that are still ongoing) have cast a spotlight on the fact that sex and gender can be more nuanced than simple binary indicators. These realizations are now penetrating into the scientific process, and as we seek for greater understanding of our own biology, it has become clear that a more nuanced treatment of sex and gender can be useful in many lines of research. For example, autism, as mentioned above, has a profound male bias, thus implicating biological sex as an important factor. More recent research has revealed that rates of both non-heterosexuality15-16 and gender variance9-14 are also significantly increased in autism. Our own research has found that masculinity, as reflected in the structure of the face of both males and females, is associated with increased symptom severity and increased reports of poor social functioning in individuals with autism (see Figures 1 & 2, below). These findings and observations may be related, or they might function independent of one another. In either case, they suggest an important role for sex and gender in our understanding of autism.

While our chief goal is to better understand the role of sex and gender in neurodevelopment, it is possible that we will also make new discoveries about the general biological basis of sex and gender. Because these are fundamental aspects of the human experience, we are both tremendously excited by this research opportunity, but also keenly aware of its ramifications and risks.

Terms Defined

| neurodevelopment | the continuous process of the formation and maturation of the brain from fetal development through infancy and childhood, puberty and adolescence, and into adulthood |

| sex | a categorical descriptor based on the generalized reproductive role within a species. For humans, this is inferred at birth from observation of genitalia. While most newborns can be clearly assigned as male or female, some cases (0.1-1.5%) are ambiguous and may be reported as intersex |

| sex characteristics | indicators of sex, typically divided into primary and secondary categories. These are genetic, biological, physiological, morphological, or behavioral features that are associated with typical male or female development |

| primary sex characteristics | indicators of sex that are observable at birth, such as genitalia or configuration of sex chromosomes (i.e., karyotype - for example, XX female or XY male, though there are additional possibilities) |

| secondary sex characteristics | indicators of sex that typically emerge after birth, usually during puberty, and usually with a greater spectrum of variability than primary sex characteristics have. These include changes in patterns of body hair growth, breast and muscle development, distribution of body fat, voice development, sexual attraction, etc. |

| sexual orientation | indicators of sex that typically emerge after birth, usually during puberty, and usually with a greater spectrum of variability than primary sex characteristics have. These include changes in patterns of body hair growth, breast and muscle development, distribution of body fat, voice development, sexual attraction, etc. |

| gender | the behavioral norms for each sex that emerge at the population level, driven by a combination of biological, social, and cultural influences |

| gender identity |

the relation of an individual to gender norms that is most consistent with that individual's feelings, perspectives, and behaviors

|

Further definitions of LGBTQ+ related terms can be found here:

Frequently Asked Questions

What role does the LGBTQ community play in guiding this research?

With the rapid expansion of genomic technologies, it is inevitable that research will be conducted into the genetic basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. In fact, much of this research is already in progress at institutions around the world. It is important to us that this research be conducted in close coordination with stakeholders in the LGBTQ community so that research plans take into account their suggestions, concerns, and anticipated risks. Specifically, our research plan provides for the following:

- our research team includes scientists who are members of the LGBTQ community

- we have conducted a survey to collect the viewpoints of the LGBTQ community on genetic and mental health research

- a community advisory council (CAC) is recruited from among survey respondents who elected to send us their contact information

- we work closely with and solicit input from healthcare professionals who are members of the LGBTQ community

- the LGBTQ community is well-represented among our scientific collaborators on this project

What is your approach?

Our initial research will study variation in sex and gender characteristics in independent adults with autism who volunteer for the study. These volunteers will take assessments that provide information on sex characteristics, gender, and sexual orientation. We will investigate whether genetic variation can explain some of the observed differences in these measures. We will also investigate whether variation in sex and gender has a modifying effect on ASD symptoms and their severity.

Because gender identity and sexual orientation in particular are highly experiential, subjective phenomena, much of the data we collect will be through self-report, using assessments developed by experts and with stakeholder input. We will augment this self-report data with more objective measures of sex characteristics, such as facial masculinity, which is computed using a facial photograph. In our own research, we found this quantitative score of facial masculinity to be predictive of symptom severity in autism in both males and females.

When outlining our scientific approach to this research, it is also important to emphasize that we have no agenda. We form hypotheses based on current knowledge, we collect data, and we analyze that data to determine whether it tends to support or refute our hypotheses. We strongly support our partners in the LGBTQ community, and the first priority in our relationship is to ensure that voices are heard and risks are minimized. At the same time, as scientists, the integrity of our process is vital, and we will not coerce our findings into conclusions that we think will satisfy one community or another.

What steps are you taking to communicate results clearly and to avoid misrepresentation?

Our community advisory council (CAC) is made up of members from the stakeholder communities (in this case, LGBTQ and ASD). One purpose of the CAC is to help us anticipate how the community will respond to the results of our research, before it is published. By previewing results to the CAC, we can develop messaging that is scientifically accurate, but that also reduces risks and addresses concerns raised.

Because journalists and science writers are a critical link in the chain of communicating science back to the general public, we will also hold a focus group with these professionals. This will address the challenges of communicating results that have a risk of misuse or abuse, and will lead to the development of a plan to ensure accurate communication of results, specifically on this topic.

We will also update our website with results of these studies, written in a layperson-friendly way, so that the public has a primary, authoritative source that presents the findings, as well as the limitations, of our studies.

How might this research benefit the LGBTQ and ASD communities?

Although many from the LGBTQ community do not look to biology to validate their experiences, if our research results in additional support for a biological basis of diversity in gender identity and sexuality, that may lead to increased acceptance among non-LGBTQ individuals. In addition, an increased understanding of the biological basis for diversity in sex and gender would contribute to better and more individualized health care for members of the LGBTQ community.

With regard to the ASD community, our research aims to better understand the biology of neurodevelopment so that therapeutic options can be better tailored to individual needs. Some members of the ASD community are rightly concerned about outsiders confusing the identity-oriented aspects of autism (e.g., personality and preferences) with the disabling aspects of autism (e.g., seizures, sleep and gastrointestinal problems, self-harm, etc.). Our goal in better understanding autism is to enable therapeutic options that focus on the disabling aspects, and not on the identity aspects.

What are the risks to the LGBTQ community, and what steps are you taking to minimize those risks?

It is possible that in the course of our research, we may discover that certain genetic variants are linked to both mental illness and either sexual orientation or gender identity. Geneticists call this phenomenon pleiotropy, which means that a genetic variant affects multiple traits. This is well-established phenomenon and does not imply a value statement on the linked traits. On a larger scale, a similar concept called genetic correlation can quantify how much of a genetic basis two different traits share. For instance, previous research has found a positive genetic correlation between risk for autism and educational attainment17, as well as risk for schizophrenia and creativity18. These examples demonstrate that sometimes traits that are generally seen as a liability share a basis with traits that are considered desirable. Consequently, just because two traits share a genetic basis does not automatically imply a value judgment through "guilt by association".

However, we recognize that these kinds of nuances are often lost in the process of communicating science to the public. In some cases, the nuance is willfully removed to promote a particular agenda. As outlined above, our goal is to mitigate this possibility through a proactive approach to science communication that involves community stakeholders. We cannot guarantee that the results of our research, once in the hands of the public, will remain free of biased interpretation. However, because this area of research is ongoing at institutions around the world, this reality exists whether or not we participate. We hope that by making a research contribution that is both scientifically rigorous and informed by community perspectives, we can minimize the potential risks inherent in this line of inquiry.

More questions? Please don't hesitate to contact our research team at michaelson-lab@uiowa.edu or at 319.335.8882.

Recommend Reading & Literature Cited

1 Sex differences in autism spectrum disorders: A review

This article provides a summary of theories and research into the male bias of autism.

2 Genes and pathways regulated by androgens in human neural cells, potential candidates for the male excess in autism spectrum disorder

Researchers analyzed gene expression differences from neural cells treated with androgens like testosterone, and they found differential expression in some genes implicated in autism. For a summary of this paper, click here.

3 Sex differences in the developing brain as a source of inherent risk

This is a review article of sex differences in neurodevelopment.

4 Neurobiology of gender identity and sexual orientation

This article is an organized review of the neurobiology of gender identity and sexual orientation. It discusses the influence of hormones in gender identity and sexual orientation, which ties in well with our hypothesis that related hormonal variation correlate with both gender identity/sexual orientation and autism.

5 The biological contributions to gender identity and gender diversity: bringing data to the table

Research in gender identity has mostly been focused on single genes; however, a recent group was established to have a big data, genomics approach to gender identity. This article provides a summary of genetic research and heritability studies of gender identity.

6 Sexual orientation, controversy, and science

This article provides an expansive summary of research in sexual orientation and would be a great place to start if interested in the subject.

7 Deep neural networks are more accurate than humans at detecting sexual orientation from facial images

Researchers developed a deep neural network using facial images from dating sites to predict sexual orientation, which is somewhat similar to our facial masculinity tool that predicts autism risk. For a summary of this paper, click here.

8 Large genome-wide analysis of sexual orientation identifies for the first time variants associated with non-heterosexual behavior and reveals overlap with heterosexual reproductive traits

A recent presentation (yet to be published) at the American Society of Human Genetics showed their results from a genome-wide association study of 493,001 individuals and found 4 SNPs significantly associated with non-heterosexuality. You can check out the abstract of the presentation and a review article by Science News.

9 Jacobs, L. A., Rachlin, K., Erickson-Schroth, L. & Janssen, A. Gender Dysphoria and Co-Occurring Autism Spectrum Disorders: Review, Case Examples, and Treatment Considerations. LGBT health, 1, 277-282, doi:10.1089/lgbt.2013.0045 (2014).

10 Vermaat, L. E. W. et al. Self-Reported Autism Spectrum Disorder Symptoms Among Adults Referred to a Gender Identity Clinic. LGBT health, doi:10.1089/lgbt.2017.0178 (2018).

11 van der Miesen, A. I. R., Hurley, H., Bal, A. M. & de Vries, A. L. C. Prevalence of the Wish to be of the Opposite Gender in Adolescents and Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Archives of sexual behavior, doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1218-3 (2018).

12 Heylens, G. et al. The Co-occurrence of Gender Dysphoria and Autism Spectrum Disorder in Adults: An Analysis of Cross-Sectional and Clinical Chart Data. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 48, 2217-2223, doi:10.1007/s10803-018-3480-6 (2018).

13 van der Miesen, A. I. R., de Vries, A. L. C., Steensma, T. D. & Hartman, C. A. Autistic Symptoms in Children and Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 48, 1537-1548, doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3417-5 (2018).

14 George, R. & Stokes, M. A. Gender identity and sexual orientation in autism spectrum disorder. Autism: The international journal of research and practice, 1362361317714587, doi:10.1177/1362361317714587 (2017).

15 George, R. & Stokes, M. A. Sexual Orientation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism research: Official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 11, 133-141, doi:10.1002/aur.1892 (2018).

16 George, R. & Stokes, M. A. A Quantitative Analysis of Mental Health Among Sexual and Gender Minority Groups in ASD. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 48, 2052-2063, doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3469-1 (2018).

17 Varun Warrier, Richard A.I. Bethlehem, Daniel Geschwind, Simon Baron-Cohen. Genetic overlap between educational attainment, schizophrenia and autism. bioRxiv 093575; doi: 10.1101/093575

18 Power, R. A., Steinberg, S., Bjornsdottir, G., Rietveld, C. A., Abdellaoui, A., Nivard, M. M., … Stefansson, K. (2015). Polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder predict creativity. Nature Neuroscience, 18, 953. doi: 10.1038/nn.4040